San Diego Union Tribune

Retired cop walked the beat starting in 1945

By Lyndsay Winkley•Contact Reporter

November 29, 2013, 12:00 PM |SAN DIEGO

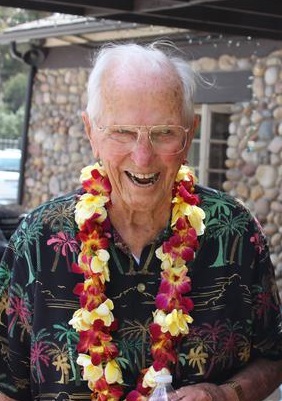

Frank Schmidt, a 99-year-old retired police officer, is the oldest member of the San Diego Retired Fire and Police Association — and he has the badge number to prove it.

“My number was 373,” he said.

Tom Giaquinto, a chief archivist for the San Diego Police Historical Association and a retired police lieutenant, said that badge number doesn’t mean Schmidt was the city’s 373rd police officer, but it’s a notably low number.

Schmidt, who will turn 100 in June, served 22 years as a police officer from 1945 to 1967 and is the fourth oldest retiree receiving a benefit from the city of San Diego’s employee retirement system.

He recently settled into his armchair, in a Lemon Grove retirement home with his dog Rio by his side, and painted a picture of his time on the force. The memories he shared were staged in a vintage version of the city, when the tuna industry was booming, thousands of uniformed service members flooded downtown San Diego on weekends and bail to get out of the drunk tank was $10.

“We didn’t get the guff from the juveniles that they do now, or the guff from anybody,” he said. “Someplace along the line I think we had a hell of a lot more respect then they do now.”

It was a different age when Schmidt was on the force as a patrolman and then as a traffic accident investigator, he said. Officers weren’t as specialized as they are now. They weren’t as educated. And they didn’t get any overtime.

Back then, new officers didn’t attend a police academy before starting the job. Training lasted six weeks from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. and, after a dinner break, they worked an eight-hour night patrol shift to learn the ropes from 7 p.m. to 3 a.m.

“Then we’d go home and do it all again the next day,” he said. “No extra pay, no nothing.”

They also paid for their own uniforms, unless like Schmidt you were lucky enough to inherit a locker from a former officer. “I got a heck of a good rain suit out of it,” he said.

When Schmidt was on patrol, officers still walked their beats, carrying among other things a blackjack, handcuffs and a lockbox key.

Officers used call boxes scattered throughout the city to stay in contact with headquarters and you couldn’t open them without a key.

“If you didn’t have it during lineup, it could result in a reprimand or a suspension,” Giaquinto said. “This was your lifeline, when so few people had telephones.”

But Schmidt said most nights you didn’t have time to reach a call box if something came up.

“Walking downtown, you’d frequently get in a beef, and you either shuffled it off or you dominated the situation and that was all there was to it,” he said.

Schmidt said outside of target practice he never fired his gun.

Officers he worked with had more flexibility, Schmidt said. They weren’t as hampered by rules and regulations, allowing them to exercise what he called “common horse sense.”

“We had more freedom,” he said. “If that’s the proper word for it.”

A lot has changed. Communication technology, the number of women on the force, and the caliber of cars driven.

Not everything is different though.

Schmidt said they still had bad apples on the force and Giaquinto said the types of crimes and criminals were remarkably similar to today.

Giaquinto, who has known the retiree for about 40 years, said although he never served with Schmidt, he can’t imagine him being anything less than congenial — even when he was writing a ticket.

“You can see by his size that if he had to meet the test he would,” he said. “But he wouldn’t be one to incite and degrade.”

Schmidt is married with three children. His wife lives in an Alzheimer’s care facility in San Diego’s El Cerrito neighborhood.

Giaquinto said the life of a police officer is physical and hard, and the ones that last are increasingly rare.

“They are some of the best people, the most compassionate people, the Frank Schmidts,” he said.

It’s been nearly 50 years since Schmidt was an officer, but he is still reverent of his time on the force and for those who serve today.

“I was always conscious of that badge,” he said. “I was proud to be a policeman.”