By KRISTINA DAVIS

JUNE 8, 2009

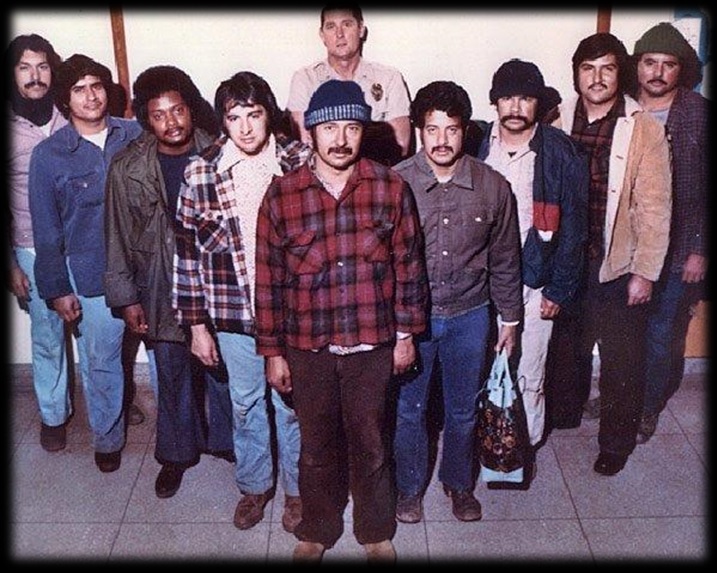

San Diego police Lt. Dick Snider (back) persuaded then-Police Chief Bill Kolender to start the Border Area Robbery Force, which included Carlos Chacon (second from left). (Courtesy of Ernie Salgado)

DETAILS

Border Area Robbery Force

Formed: October 1976 to stop assaults on border crossers

Disbanded: May 1978

Members: 10 officers and one sergeant

Shootings: About 16, including six major shootouts

Arrests: More than 300, including Mexican officers

San Diego officers wounded: 3

Claim to fame: Subject of Joseph Wambaugh's best-seller “Lines and Shadows.”

In the spring of 1976, as the nation prepared to celebrate its bicentennial and Jimmy Carter campaigned for the presidency, officers from San Diego's 86th police academy left the classroom and began their rookie year.

Dressed in the crisp khaki uniform of the time, Officer Carlos Chacon spent his shifts chasing criminals and learning the city's back alleys.

But after six months on the job, a lieutenant had other plans for the intense 23-year-old.

How would the kid from Otay like to join an experimental team of other Latino officers and spend nights crawling around the border canyons? The elite squad would hunt robbers who were leaving scores of illegal immigrants maimed or dead.

By saying yes, Chacon had no clue how much the assignment would shape his career. How many shootouts he would have under his belt in his first year. Or how the team's exploits, for better or worse, would become the subject of Joseph Wambaugh's best-selling book “Lines and Shadows.”

More than 33 years later, Sgt. Chacon will retire this month from the San Diego Police Department.

He is the last of the 11 original members of the Border Area Robbery Force to leave the department.

“It's been glorious. I've had a charmed career,” Chacon, 56, said in a recent interview. “I love this place, love this job.”

Dangerous canyons

In the mid-1970s, San Diego's canyons had become a death trap of nightly stabbings, shootings, beatings and rapes as bandits from Mexico terrorized immigrants making the journey north.

The robberies were making headlines and San Diego police Lt. Dick Snider persuaded then-Police Chief Bill Kolender to start the team.

It didn't take long for someone to realize that the acronym for Border Area Robbery Force was BARF, and the name stuck.

Chacon and an academy classmate joined veteran officers for training in military-style tactics at Camp Elliott, an old Marine Corps range near Tierrasanta.

The assignment took on a special meaning for Chacon, who thought about his mother's journey decades earlier when she illegally crossed the Rio Grande into Texas with his three older brothers.

For its first three months, the team dressed in camouflage and moved through the canyons in the dark among the cactuses, rattlesnakes and raw sewage. They rarely got close enough for a bust before the robbers returned to Mexico.

They realized they would have to become the victims to get close enough.

The officers shopped at thrift stores for beanie caps, old jeans and long-sleeved denim shirts. A worn sports coat hid the modified sawed-off shotgun that Chacon often carried.

They smoked Mexican cigarettes and let their hair grow wild.

It worked. Confrontations occurred several times a week, often ending in foot chases and gunfire.

“It was akin to being in a war,” said BARF member Rene Camacho, now a consular liaison detective with the Sheriff's Department. “I'll never forget the shootings, being robbed. The feeling of not knowing what's going to happen in the next second.”

Camacho was standing next to Chacon when the rookie officer was shot.

The team was hanging out at an area of the border fence where two Tijuana police officers were known to extort immigrants before they crossed.

“One was pointing his gun at us, ordering us to come back to the Mexican side,” Chacon said. “He kept rocking his gun back and forth.”

Chacon's sergeant, Manny Lopez, responded in Spanish by telling the Mexican cop that he didn't have the authority to order them anywhere. Lopez never let on that they were cops.

The Mexicans, growing frustrated, then decided to cross the border and drag the group back, Chacon said.

It turned into an armed standoff between Lopez and one officer, and the Mexican cop fired. The bullet ricocheted off the nylon shoulder strap of Lopez's bullet-resistant vest.

“Of course, everyone starts shooting,” Chacon said.

He saw one of the Mexicans look at him and fire.

“I felt dirt in my face and my arm felt like someone kicked me,” Chacon said. “I was looking at one of the officer's stomachs in the flash, and aimed and fired.”

One of the wounded Mexicans was taken away in an ambulance, but the other escaped into Tijuana. Meanwhile, the sky above Tijuana glowed red and blue and sirens wailed as hundreds of Mexican officers responded to join the gunfight.

Chacon was treated for a bullet wound to his right arm.

The shootout strained relations between the United States and Mexico as their police forces clashed more frequently in the canyons.

Taking a toll

Nineteen months after the experiment began, Chief Kolender decided it had grown too dangerous to continue.

By then, the team had arrested more than 300 people – some of them Mexican law enforcement members – and logged about 16 shootings. Three of the team members had been shot.

“A lot of lives were saved and crime was down considerably in the border area,” said Kolender, who is retiring this month after 14 years as San Diego County sheriff. “They sacrificed a lot to do this.”

The news media hailed the San Diego officers as heroes, but the team members were quietly struggling with personal demons that came with being exposed to too much violence, death, fear, boozing and womanizing.

“We all changed,” Chacon said. “When we started, we were all very close. But the stress took its toll on every single individual.”

When Los Angeles police officer-turned-author Joseph Wambaugh began to talk to the officers a few years later, he thought he had stumbled on a modern-day tale of the Old West.

“They were a throwback to 19th-century lawmen out in those canyons with a badge and a gun. They were the last of the gunslingers,” said Wambaugh, who lives in Point Loma.

“It's a difficult task to get handed to you when you're a young man thinking you're a cop doing police work, and suddenly you're out there being Wyatt Earp.”

In interviews for the book, Wambaugh said it was apparent the officers never decompressed from the experience. Most of their marriages fell apart shortly after.

Chacon's marriage lasted longer than most, but even it succumbed to divorce in 1995. He has since remarried.

“Lines and Shadows” became a No. 1 best-seller in 1984.

Like “kids with Christmas presents,” Chacon said the team gathered in a living room one night to open a box of early copies sent by Wambaugh. The mood quickly turned sour.

“If he'd been there, he'd have been beaten within an inch of his life,” recalled Chacon, who said he has never read the entire book.

Perhaps most infuriating were the numerous accounts of the officers'extramarital escapades that had been hidden from their wives.

After the dust settled, most of the other members conceded the portrayal was pretty accurate and are proud of the book.

When BARF disbanded, the team became the department's first unofficial gang and narcotics squad – yet another plum assignment for an officer with two years on the force and little patrol experience.

Eventually, Chacon asked to return to being a patrol officer in Southern Division, which includes Otay Mesa and San Ysidro.

During his long career, Chacon worked in many units throughout the department, including vice, special investigations, intelligence and as a Mexican liaison

officer. He has spent the past three years in the department's special-events unit.

Chacon said his proudest moment as an officer didn't happen in the canyons; it came when he arrested a Latino protester during a border standoff with the Ku Klux Klan. The protester had taken a rock and smashed the windshield of a car full of KKK members who were trying to leave.

“I didn't take sides. I demonstrated that I was professional and unbiased as I could be,” he said. “It was a defining moment for me as far as what we're here for as cops.”

S.D. police’s border unit ‘last of the gunslingers’

Retiring sergeant looks back on days with mid-1970s squad