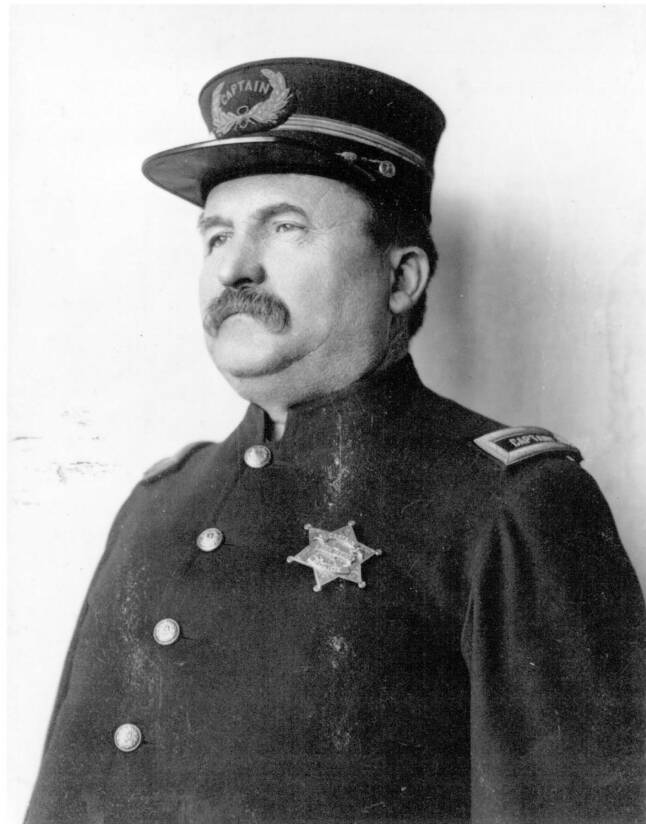

BARTHOLOMEW MORIARTY

With Gary E. Mitrovich

Law enforcement is in the blood of the Irish. For generations, they have been part of a tradition. Residents of larger American cities - New York and Chicago, for example - know this legacy well. The Irish have been part of San Diego's law enforcement community as well. And, if there is a patron saint for San Diego's Irish cops, then it must be one Bartholomew "Mory" Moriarty. A faithful, revered veteran, Moriarty was among the original 11 men chosen to protect and serve the SDPD.

Moriarty was born in Dingle County, Kerry, Ireland. After immigrating to the United States, he drifted west and settled in San Diego. His first job was as a bricklayer in the construction of a hospital at Seventh Avenue and Market Street. Moriarty's first wife died. He later remarried Katherine Barron and had two children. Their daughter, Marguerite later married the son of the ninth SDPD Chief of Police, William Neely.

In November 1886, Marshal Coyne had given his little force some structure. He ordered new badges with "Police San Diego" inscribed on the face. Coyne numbered them - 12 through 30 - and purchased batons, handcuffs, and whistles for his deputy city marshals. Marshal Coyne seemed to sense a change in the wind, that little San Diego would soon have its first, official, sanctioned police department.

In 1889 unhappy citizens drew up the City Charter that essentially survives today. Among other branches of government, the new charter established a police department and a chief of police to replace the city marshal system. A four-man Board of Police Commissioners, presided over by the mayor, would appoint a chief. This appointment would have to be approved by a Common Council of elected officials. The Chief would serve a two-year term, then be up for reappointment or dismissal.

The new City Charter went into effect on May 16, 1889 - and thus was born the San Diego Police Department. A few days later, the first 11 SDPD officers were announced - Bartholomew Moriarty was one of those men.

Moriarty pulled the City Jail as his very first assignment, documented on the duty roster prepared by Chief Coyne in October 1889. Moriarty was later appointed the first bailiff and clerk of the Police Court. There he was admired for his penmanship, keeping the docket in a fat round hand. Working for Police Judge Thomas Hayes, Moriarty filed the court's monthly reports to the Common Council. He filled out subpoenas and kept track of complaints, warrants, and summons. Judge Hayes liked the cop's work and his jovial presence in the courtroom.

Shortly before 1897, the Police Commission made a decision that would shortly send Moriarty into the center of a political fracas. The Board determined that, while the City Charter required the Police Department to furnish a court bailiff, this officer was not compelled to act as the clerk of the court, a job they hardly classified as police work. A resolution ordered the bailiff to report for duty at the police station immediately after his court duties were concluded. Further, the policeman/bailiff was specifically instructed not to do the clerk's work.

Chief Jacob Brenning chose not to enforce the resolution so Moriarty continued to display his fine penmanship on court records. But, when James Russell took the chief's office, he immediately ordered Moriarty to comply with the City Charter. The stage was set for a battle royale between Chief and Judge - with Moriarty stuck right in the middle.

Moriarty was recalled as a man who always kept his counsel and never stuck his neck out. He hated politics and would have no hand in it. And he separated his work life from his home life. According to his daughter, Moriarty did not speak of his job with his children, though she can vividly remember her father riding his bicycle home from the police station in the late afternoons.

A brave a man who never walked away from trouble, Moriarty once was taking a prisoner to jail when he lurched and fell off a curb. In doing so, he fractured his leg, but held on to his prisoner until help arrived.

Moriarty was a respected and well-known officer in the community. On one occasion, the bartender at Pete Cassidy's saloon called the police station and asked for Moriarty. The caller was adamant - only Moriarty could restore the peace and no one else would do. When the cop arrived at the saloon on the west side of 400 Fifth Street, he discovered that a drunk had gone berserk there. Moriarty immediately recognized the troublemaker from past contacts. He stepped up to the intoxicated man and looked him calmly in the eye.

"What's the matter with you?" asked the Irish cop. That was all it took - the drunk ceased his disruptive behavior and gave himself up to Moriarty without further incident.

Officer Moriarty was promoted to Sergeant on January 7, 1903. This included a $15 raise - from $80 to $95 a month! Moriarty was assigned to the front desk at Police Headquarters, on the ground floor of the old City Hall building, still standing at the southwest corner of Fifth and "G" Streets. For a real feeling of the period, we step back into time with the descriptive words of Herbert C. Hensley, a newspaper journalist of the era:

At the far end, opposite the door, was the elevator, not very dependable. The entry hall wasn't very large and a narrow part separated by a counter constituted the police station. At the farther end, Sergeant Moriarty sat heavily. He was stout - even fat - and most of the time he had little or nothing to do. He was good-natured and tried to be obliging; I always got along finely with him, and he always seemed rather embarrassed when he couldn't give me any news, even apologetic.

I said Desk Sergeant Moriarty sat `heavily.' That was the general impression one got of his habitual attitude...

Though reporter Hensley was rather "heavy" on his characterization of Moriarty, he did share an example of the sergeant's latent agility. It seems a couple of boys - one in his teens and the other quite younger - entered HQ bearing signs of a dispute, with tears staining the face of the littler lad. The two approached the front desk and stood silently for big Sergeant Moriarty, who swiveled about to face them. There was a trace of annoyance on his own features.

"Now boys," he declared impressively, "you'll have to be quiet in here. I won't have any disturbance. You," he addressed the bigger boy, "tell me what's the matter."

"Well, it's this way," he said earnestly, "I had a nice, well-behaved snake that I caught and he was a fine pet. I thought a lot of him. Then this little chap here," he motioned to the smaller one, "sees that snake and nothing will do be he must have him... and I sold it to him for two bits. [That's 25 cents, for those who may have wondered...] "That's 10 cents a foot - he's two-and-one-half feet long, which he said was a fair price. So I gave him the snake.

"Then right away I saw the little bugger [referring to the boy again] didn't know anything about a snake and wasn't taking care of it properly. I could see the snake wants to come back to me. So I took him back and offered to pay back the two bits... but he won't take it. Don't you think it was perfectly proper, Sergeant Moriarty, for me to take the snake back if I paid back the money? Here, I'll offer it to him again in your presence."

The teenager shifted something in his right hand to his left and took a coin out of his pocket. He held the quarter out to his little friend, who promptly slapped it out of his hand.

"Boys, boys!" commanded the sergeant, "I won't have any quarreling in here. You shouldn't play with a snake anyway...” His voice trailed off as Moriarty became aware of something in the older boy's left hand. "What's that you're holding at your side?"

It was the snake itself, the subject of this debate and, until now, it had been hanging docilely in the boy's hand, held in midsection. It was a good-sized gopher snake, really harmless. Sensing the shift in focus, the reptile suddenly tensed up and stuck its head and part of its body up onto the counter, in the direction of a now startled Desk Sergeant. Again, Hensley's description is best: “ With a look of horror, Moriarty sprung from his chair, at the same time snatching open the top drawer of his desk, exposing to view his big black revolver. He grasped the weapon and half drew it out.

“Get that snake out of here or I'll shoot it!"

"Aw, it ain’t poisonous," placated the big kid. "He ain't a rattler. He won't hurt you, Mr. Moriarty."

"No matter," stated the cop loudly, backing as far away as he could in that little room, "you get out of here and take that snake with you before I shoot him!"

The boys fled without resolution to their dispute. Hensley doubted a gang of bank robbers could not have riled Moriarty so.

Moriarty holds the honor of being the first captain ever appointed on the San Diego Police Department. He was prompted in 1907.

Two years later he received another promotion, albeit only a temporary one.

"CAPTAIN MORIARTY IS NEW CHIEF," announced the Union, but the headline was misleading. Chief Neely had tended his resignation and the Police Commission had accepted it as such. They appointed Moriarty an "acting" chief until a decision could be reached.

Days later, Jefferson "Keno" Wilson (1909-1917) was appointed.

By 1912, rapid population growth and the boom of the automobile had pushed the city's limits east, to Boundary Street in North Park. Chief Wilson chose to decentralize to meet the demands of an ever-expanding town. He opened the very first police sub-station, in Hillcrest, in the firehouse at Ninth Street and University Avenue. Then Wilson put Captain Moriarty in charge.

Moriarty worked the 8 a.m. to 5 p.m shift, with a staff of two-foot patrolmen and one motorcycle officer. He had a direct phone on the desk in the tiny first floor office of the fire station. Patrolmen were supposed to call in on the hour, as they made their rounds. A senior patrolman was assigned to the desk from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.

Footmen made their rounds in the mid-watch and graveyard shifts.

The little sub-station also boasted an iron cage, installed to hold prisoners pending their transport downtown. Chief Wilson's 1912 Annual Report listed it under "expenses - including prisoner's cage at sub-station: $206.42."

One of the first foot patrolmen later admitted to a bit of mischief during his Hillcrest watch. The officer would walk his beat for a short while, then sneak back to the station to play cards upstairs with the firemen on shift. He would make his call-ins from an upstairs phone to the desk officer below.

On May 27, 1916, Moriarty retired from the force, after 27 years as a city police officer. It was routine event, considering he was one of the charter members of the San Diego Police Department. But that was probably the way Moriarty wanted it.

Moriarty had few specific plans for his retirement, but he was keen on visiting his sister in Australia. A city rule prevented him from doing so. In those days, a city pensioner was required to appear in person at city hall every month, in order to sign their paycheck. No signature - no money. City officials would not give Moriarty three months leave nor would they allow him to sign ahead or upon return. So Moriarty never made that trip.

Bartholomew Moriarty died on April 5, 1933. Five motorcycles led the funeral procession to Holy Cross Cemetery, where internment was made. A life-long Catholic, Moriarty was a charter member of the San Diego Council of the Knights of Columbus and a member of the Third Order of St. Francis. As such, Moriarty was buried in the Franciscan robes, the first San Diego member to receive permission to be buried in the robes of that Order.

Each year, as the contingent of San Diego police officers marches in the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade, they pay silent yet unknowing homage to the very first Irish cop on the Department, one of the original 11 officers - Bartholomew Moriarty.

THE THIN BLUE LINE

A/CHIEF BARTHOLOMEW MORIARTY (05/01/1909 - 05/02/1909)

BADGE 4

SDPD 1889 - 05/27/1916

06/1861 - 04/05/1933

Basic information is provided as a courtesy and is obtained from a variety of sources including public data, museum files and or other mediums. While the San Diego Police Historical Association strives for accuracy, there can be issues beyond our control which renders us unable to attest to the veracity of what is presented. More specific information may be available if research is conducted. Research is done at a cost of $50 per hour with no assurances of the outcome. For additional info please contact us.